Minimum Price Contract What It is How It Works Example

Contents

Minimum Price Contract: What It is, How It Works, Example

What Is a Minimum Price Contract?

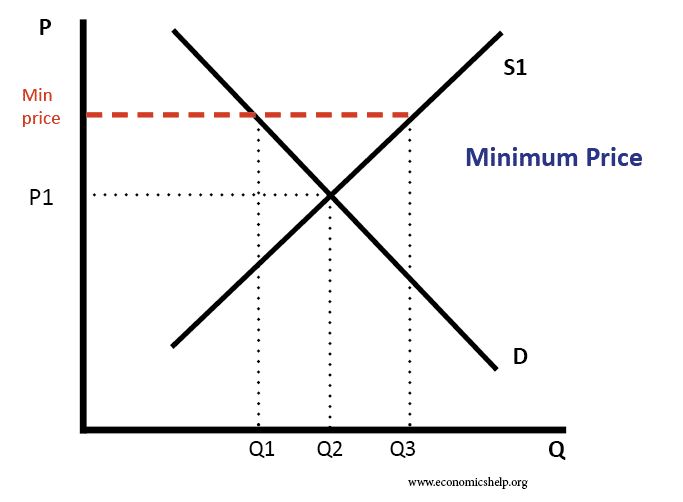

A minimum price contract guarantees the seller a minimum price at delivery. This type of contract is used to protect producers from price fluctuations in the market, especially in agricultural sales such as grain.

A minimum price is specified to account for the possibility of spoilage and loss of value in agricultural products if not distributed promptly.

Key Takeaways:

- A minimum price contract guarantees a price floor upon delivery of the underlying asset.

- This arrangement is common for agricultural derivatives due to the risk of spoilage, which can erode market value.

- A minimum price contract specifies the quantity, minimum price, and delivery period for the underlying commodity.

Understanding a Minimum Price Contract

A minimum price contract allows agricultural producers to determine the amount of product to store and the quantity to unload to receive an acceptable price.

The contract includes details such as the quantity, quality, minimum price, and delivery period for the specified commodity. Sellers also have the option to sell above the set minimum during a specific period, similar to a put option in trading.

Delivery marks the final stage of a minimum price contract. The price and maturity are determined on the transaction date. On the maturity date, the seller must deliver the commodity, unless the transaction has been closed out or reversed with an offsetting option.

Example of a Minimum Price Contract

A soybean grower sells 100 bushels of soybeans to Company A in June. The cash delivered price is $6.00 per bushel. The grower includes a December call option with a strike price of $8.00. As part of the contract, the grower pays a $.50 premium per bushel and a $.05 service fee.

The guaranteed minimum price per bushel is calculated as $5.45 ($6.00 – $.55), which includes the premium and service fee.

If the price of soybeans rises to $9.00 in December, the $8.00 call is worth $1.00. This difference is added to the minimum price, resulting in a total guaranteed price of $6.45 per bushel.

In another scenario, if the price of soybeans only reaches $7.00 in December, the call option is worthless as the futures price is lower than the strike price. In this case, the grower receives the minimum price of $5.45.

The disadvantage of the contract in the second scenario is evident. The seller pays a $.50 premium and a $.05 service fee for a call option that does not yield a better price for their crop. Without these fees, the seller could have potentially made a higher profit.